How Medications Stay: Doctor Day in Long-Term Care

Two vignettes—Ativan and Teva—offer a closer look at the routines that hold polypharmacy in place.

This post builds on my previous entry about the nurses’ room—not just as a hub, but as an active site where the routines, forms, and relationships that sustain polypharmacy are produced and held together. Here, I shift focus from the space itself to what happens in it—specifically during Doctor Day, when medication decisions are revisited, questioned, and often reaffirmed.

Every week, for several hours, a physician visits each floor of the long-term care facility. Staff refer to it simply as Doctor Day. On the surface, it’s a practical arrangement: the physician responds to urgent concerns, signs forms, and makes decisions about medication. But beneath that, Doctor Day is a complex choreography—an encounter shaped by relationships, paperwork, stories, memories, silences, and the material infrastructure of care.

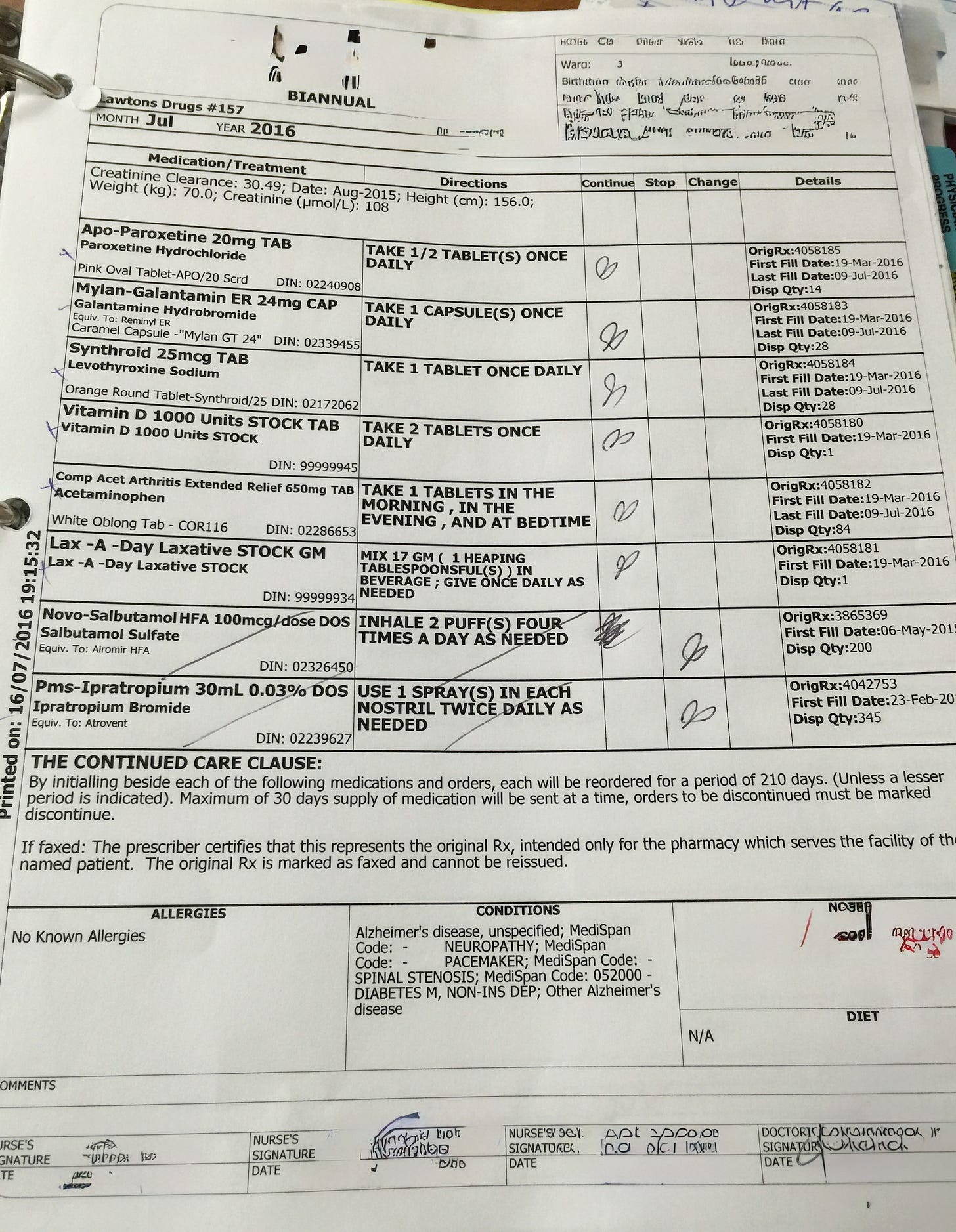

One of the central tasks during Doctor Day is the completion of the bi-annual medication review form—a routine requirement that keeps the flow of medications legally and practically intact. But this task is more than administrative. As one physician put it, the bi-annual is also a moment to “dig a little deeper”—to pause, however briefly, and reflect on what the resident is taking, why, and whether anything should change. These forms create an opening—a narrow one—for reconsideration amidst the flow.

Why is this important? These scenes might seem like small moments, but they reveal a lot. They show how medication decisions actually happen—not in abstract policy discussions or prescribing guidelines, but in the middle of paperwork, habits, jokes, hierarchy, professional and institutional routines. This is how polypharmacy is made real, and why it’s so hard to undo.

What follows are two close-up vignettes—Ativan and Teva—each capturing how medication decisions are made in the everyday context of Doctor Day. These scenes are followed by a reflection on what they reveal about how polypharmacy is sustained, negotiated, and occasionally unsettled in long-term care.

Image of BIANNUAL form (De-identified)

Vignette 1: Ativan

[Begin Vignette 1]

[On the table several binders are open and a small stack of bi-annuals]

[doctor touches and reads the bi-annual form and then moves her body and eyes towards the maroon binder]

Doctor: OK, how about [first name of resident], how are her bowels?

[the LPN is trying to answer a question from the nurse about who is on call and is writing a note on a piece of paper and is finishing giving medications to a resident who is standing by the door]

Doctor: Are they ok?

[Doctor slightly turns her face to CCA in the room and repeats the question about B's bowels]

CCA is about to say something and then the LPN speaks:

LPN: Her bowels.... it's hard to say, it's hit and miss. If she misses a bowel movement then [unable to capture few words] 9 out of 10 times her bowels won't have moved. You can go back and follow it.

Doctor: Oh really...

LPN: So if she is exploding I won't give the lax-a-day for a bit …

Doctor: So but she usually goes?

LPN: She'll go if you put her on the toilet. I may have given her a fleet maybe once.

Doctor: Does she get codeine at bedtime?

LPN: Yeah

Doctor: Do you want to keep it at bedtime? Or change it to earlier…19:00?

LPN: They are saying they are having a hard time getting pills in her because she is sleepy.

Doctor: What time is her bedtime? 21:00?

[LPN asks CCA what time resident goes to bed]

CCA: Depends on her day but generally she is in bed by 8 o'clock.

Doctor: Does that mean she is getting her pills or is there a lot of coercion?

LPN: [silence as nurse does not respond]

Doctor: Because if she is too drowsy why is she getting this pill?

[LPN went to adjoining room]

Doctor: So I am looking at the codeine here...

LPN: Uhuh

Doctor: So for the most part she is comfortable. She got the amitriptyline at bedtime. She is drowsy at bedtime...hmmm, codeine only has a 4 hour action. ... Do you want to stop the bedtime? She has an as needed..

LPN: I think you can stop them all and keep the PRNs...cause if we get rid of them completely then her shoulder may flare up again. Remember that shoulder? She uses voltaren as well.

Doctor: So… lorazepam...

LPN: Now, before you mess with her Ativan … you should know she only has one sheet of medications!

Doctor: Ok, how about I not mess with it!

[Doctor has a smile on her face and looks up from the paperwork at the LPN]

LPN: Ok, I have a story to tell you and you'll appreciate it.

Doctor: Yeah [laughs]

LPN: Dr xx (the former physician for the floor) took it [Ativan] from me! We had to have a test to see who was right and who was wrong. He took it from me for two weeks and I had these spells - like 9 out of 14 days. And then he had to give it back to me cause I was constantly calling him.

[LPN laughs uproariously]

Doctor: Yeah…

LPN: It’s such a small dose but hey...

Doctor: Ok…

[It is close to 15:00 shift change and CCAs are charting. There are a total of 6 people in room, pens in hand, everyone is writing something.]

[End of Vignette 1]

Vignette 2: Ativan

[Begin Vignette 2]

Nurse sits next to physician

Doctor asks the nurse questions about Mrs J.

Doctor: About Mrs J, How is her mood?

Nurse: Hmmm, good

Doctor: Very good?

Nurse: Yeah, no worse, no better.

Doctor: Pain is controlled?

Nurse: I would say, yeah.

[Doctor focuses on maroon chart bi-annual and shifts attention between the two]

[nurse talks briefly to CCA about a resident]

Doctor: Sleep is good as well?

Nurse: All she does is sleep.

Doctor: Does she want to eat?

Nurse: Yeah

[all clear code red over the intercom announcement]

Doctor: She isn't really participating in activities, is she?

Nurse: No not really, once in a while she goes out to a music program or something.

[nurse gets up and moves to adjacent space to hand form to person coming into nurses’ room]

[doctor is scribbling in both maroon resident chart and on bi-annual]

Doctor: Was she put on Teva combo by respirologist?

[looks at nurse briefly before looking back at paper work in front of her]

[nurse does not respond]

[doctor taps with fingers on form to bring nurse attention back to the form]

Nurse: No, I think you did.

Doctor: What is Teva?

Nurse: I think it was you who put her on it.

[nurse flips through the resident chart]

Nurse: Yes, you did put her on it. She is doing pretty well.

Doctor: uhuh…

Doctor: Has she seen a respirologist?

[doctor is flipping though maroon chart]

Doctor: I see on March 9th I asked for consult. …. Oh just wait a second. Yes she did.

Nurse: Yeah, but not recently

Doctor: But she is doing well? She is not coughing.

Nurse: She is not complaining.

Doctor: How often does she cough?

Nurse: Well, every morning, but not…

Doctor: Yeah, Ok.

The doctor closes the maroon resident binder, gets up and puts it in alphabetical place with the other maroon resident binders.

[End of Vignette 2]

What the Ativan and Teva Vignettes Reveal About Polypharmacy

1. Medication Decisions Are Situated, Not Singular

The Ativan and Teva vignettes show that medication decisions in long-term care are not discrete clinical acts. They are situated practices, distributed across people, forms, silences, and timelines. There is no single moment when a physician “decides” in the abstract. Instead, decisions unfold in patterned ways—through conversation, chart-flipping, storytelling, hesitation, negotiation, and ritual.

This is what polypharmacy is—not simply “too many medications,” but an assemblage of small, mostly invisible decisions made possible by institutional routines and infrastructures. It is not accidental; it is made.

2. The Nurses’ Room as a Knowing Location

These scenes unfold in the nurses’ room, a space dense with the material and social resources that make medication decisions possible. It is not a neutral backdrop, but a working infrastructure. It houses binders, forms, digital records, jokes, interruptions, and habitual rhythms. It also enacts a kind of order—a place where the doctor and nurse co-locate to “know” the resident.

Susan Leigh Star, a sociologist whose work I return to often, reminds us that space always reflects priorities. The nurses’ room brings together what matters in the everyday care of residents: the flow of drugs, the accountability of signatures, and the temporal demand of institutional forms. It is where paperwork becomes practice.

3. Forms, Objects, and the Texture of Work

The bi-annual medication review form structures the work of Doctor Day. It is a legally and practically necessary document—if it’s not filled out on time, the flow of medications is disrupted. But it is also an opportunity: a rare, time-boxed moment to “dig a little deeper,” as one physician put it.

The form sets the tempo. The pen moves between the bi-annual and the progress notes. The MAR sheet is consulted to stabilize a memory or verify a dose. These are not mere tools of documentation; they are actors in the practice. They determine what is seen, said, and done—and in what order.

And they do more than guide care; they shape it. The content of care is often determined by what the form requires: continue, stop, or change. The ease of “continue” often outweighs the effort of “stop.”

4. Power, Hierarchy, and the Ink of the Pen

Despite the cooperative tone, power circulates through the scene in subtle and highly material ways—most visibly through the physician’s pen. Her signature authorizes action. Her initials on the bi-annual form and green progress notes legalize the continuation or cessation of a drug. Her ink is what moves a medication into or out of circulation.

And yet, that power is rarely wielded unilaterally. In the Ativan vignette, we see the nurse intervening decisively. She doesn’t argue outright. Instead, she stages a kind of narrative interruption. As the physician moves toward discussing deprescribing lorazepam, the nurse steps in—not with data or clinical rationale, but with a story. She says: “Before you mess with her Ativan… I have a story to tell you.”

It is not a story about the resident per se. It is a story about her own struggle with a previous physician over the same issue. The narrative is framed as a kind of trial-by-substitution: the doctor took the Ativan away, and she—the LPN—suffered the consequences. She says, “I had these spells,” as though she herself were the patient in withdrawal. The boundary between nurse and resident collapses.

This is not mere humour or dramatic flair. It can be understood as a form of embodied advocacy. The nurse is not just presenting clinical facts; she is re-enacting the resident’s past distress, claiming experiential knowledge that supersedes the chart. She is saying: I lived this. I know what happens when you take it away. Don’t do it again.

She is also doing something institutional: referencing the “one-sheet med list” as an index of acceptable polypharmacy levels. The bi-annual, after all, is a visual artifact; one page = eight medications. Fewer pages means fewer questions. This is another form of persuasion—pointing to legibility and acceptability rather than risk.

In the end, the physician listens. She smiles. She says, “Ok, I won’t mess with it.” The nurse wins—but not through resistance or confrontation. Through storytelling, affect, shared memory, and institutional shorthand. And while the pen still holds the formal power, it is the nurse who shapes the hand that moves it.

5. The Semantic Repertoire of Long-Term Care

Doctor Day operates within a shared semantic field. Staff use shorthand to communicate efficiently: “bowels,” “one-sheet med list,” “Ativan.” These words are not simply clinical—they are contextual, situated in the texture of long-term care.

This language enables care, but it also narrows it. It privileges what is decipherable within the institution. Concerns are framed in terms of dosage, sleepiness, agitation, and participation in activities. This is the vocabulary that gets a response—and the one that gets recorded.

6. Knowing the Resident: Fragmented, Embodied, and Substituted

Across both vignettes, the resident—the person whose medications are being adjusted or renewed—is notably absent. There is no direct consultation that we know of, no negotiation, no moment of shared decision-making with the person most affected. Instead, the resident is talked about, remembered, and approximated through stories, observations, and charts.

Is this absence neglectful or is a feature of institutional life? The resident is made present through documentation, affective recall, and conversational shorthand. In one moment, the nurse even uses her own body to describe the resident’s withdrawal symptoms, saying, “I had these spells,” effectively fusing her memory with the resident’s presumed experience.

But this is a different kind of presence—mediated, constructed, and partial. It highlights a tension at the heart of polypharmacy in LTC: while medications are administered to residents, decisions about them are often made around them.

I will return to this phenomenon in a future post.

7. Why Deprescribing Is So Difficult

In both vignettes, there is space for change—but not much movement. In the Ativan case, deprescribing is considered but politely deferred. In the Teva example, uncertainty around the drug’s origin leads not to removal, but to continuation. Neither drug is stopped.

Is this due to negligence or inattention or due to structure. The path of least resistance is to continue. Deprescribing, by contrast, introduces uncertainty, effort, documentation, and sometimes conflict. It is harder to stop than to maintain.

The bi-annual form may offer an opening, but it is narrow, fast-moving, and deeply embedded in organizational rhythms that perhaps favour the status quo.

Conclusion

What these scenes show is that polypharmacy is not just the presence of many drugs, rather it is an organizational rhythm, it’s a product of how care is organized. It is the result of forms, habits, distributed knowing, space, and partial presence (of patients). It is not just what doctors and other health care workers do, but what systems make possible.

The description of these two cases reveals so much. All the general talk in the media about oversubscribing comes to a quick conclusion- continue.

Readers will come away determined to think critically. But will that sustain itself in a real situation? We think not.