Medications in Motion: The Many Hands of Long-Term Care

In long-term care, medications don’t just appear at a resident’s bedside. Behind every prescription, every pill swallowed and every injection, there’s a carefully coordinated system of people and technology ensuring that medications are prescribed, dispensed, delivered, and administered safely.

Pharmacists process prescriptions, Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs) move through hallways with their carts, and residents themselves take on the often-overlooked work of managing their own medications. But it’s not just people—technology like the Manrex Pouch Porter system, digital records, and medication carts shape how and when medications flow through the facility.

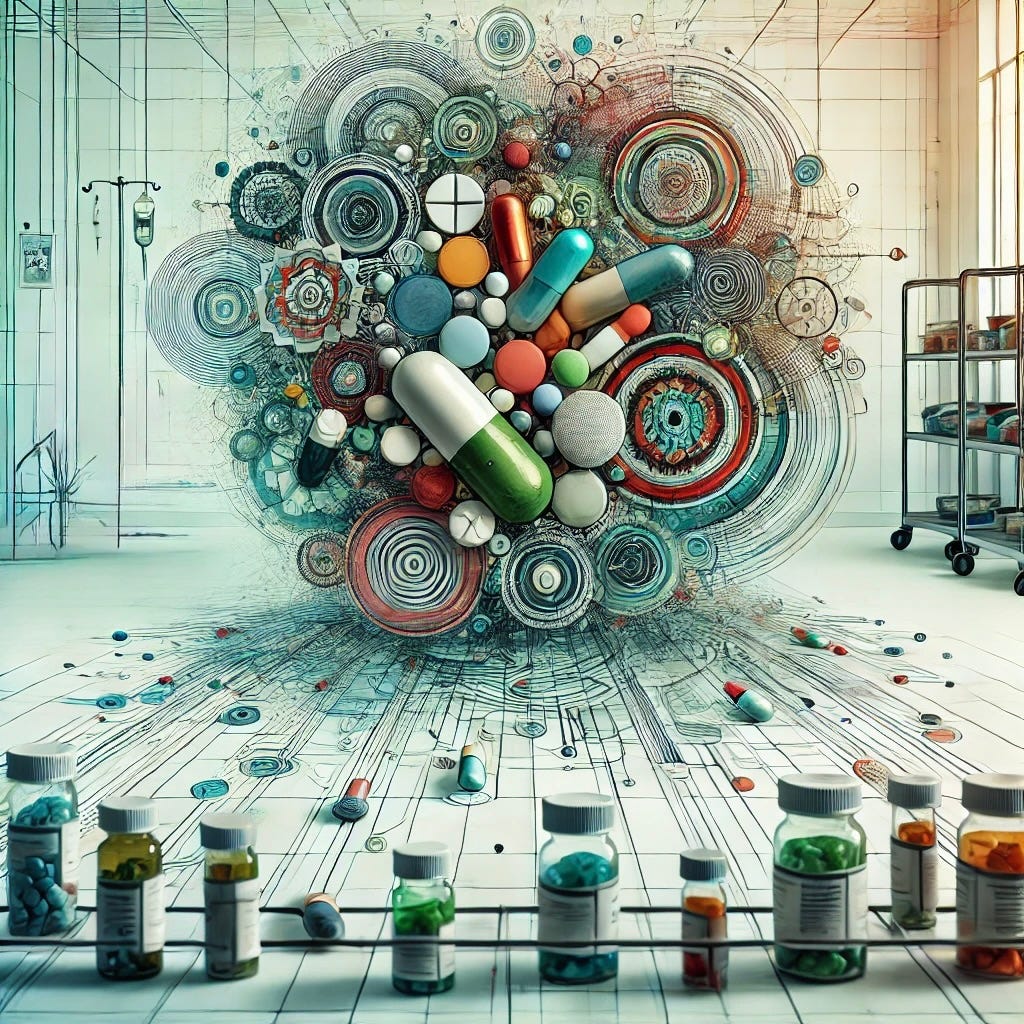

These everyday details—who does what, how technology is used, and the like—may seem mundane, but they reveal how medication management is organized, how expertise matters, and how residents experience care. My research shows that polypharmacy isn’t just about the number of medications someone takes—it’s about the entire system that enables as well as constrains medication use.

In this post, I take a closer look at the many hands—and technologies—behind medication management in long-term care:

One of the key players in accommodating the flow of medications is the pharmacy. Located within the Long-Term Care Facility (LTCF), Lawton’s pharmacy rents space on the ground floor for the processing of medications, not only for Northwood, but also for seven other LTCFs in the city. In a small space, pharmacy workers are receiving orders, checking orders, communicating with physicians, nurses and others about these orders and other related matters. The facility has a variety of equipment that allows for an output that can match the orders in a speedy manner. Orders received by 15:00 will arrive on the floor the same or next day. Couriers pick up and drop off orders and deliver batches of drugs on an ongoing basis, often accompanied by security companies and their guards.

The flow of medications is carefully managed through a variety of system mechanisms that have been implemented over the past few decades in this LTCF as well as in the broader health care system (Wong and Tscheng Date unknown; Wagner and Rust 2008; Szczepura et al. 2011). For example, the LTCF where I completed my fieldwork uses the Manrex Pouch Porter system.

Manrex’s promotional slogan is “Promoting health by preventing error.” Using the Manrex Pouch Porter system (www.manrex.com), Lawton’s fills, prepares, and counts all medications, and packages them in the Manrex Multi Dose Cellophane Pouch system. Once a week the LPNs from each floor go downstairs to Lawtons to pick up the medications in covered medium-sized plastic storage bins for the floor residents. When the LPN administers the medications to a resident, they are already organized by dose through the Manrex Multi Dose Cellophane Pouch, which remains in the pouch porter system in the medication cart for the week ahead.

Organizations assign roles to ensure work is accomplished in a strategic and efficient manner. In health care, designated scopes of practice help configure who does what, how and when. Current scopes of practice specify that physicians and nurse practitioners can legally prescribe, pharmacists fill prescriptions and do some limited prescribing, while LPNs are involved with the day-to-day managing of the medication side of care, amongst other tasks.

All staff members and residents on the floors are involved in one way or another with medications. Continuing Care Assistants (CCA) do all of the body or personal care work, which includes washing, dressing and helping administer medications during mealtimes. Their scope also allows them to apply prescribed creams to the bodies of residents. The LPNs are doing the daily routine of medication administration as the LPNs move from room to room several times a day with the medication cart, crushing pills, handing out pills or injecting insulin. Some of the medications are measured and handed out in the floor dining space during mealtimes. Each distribution is accounted for in the Medication Administration Record (MAR).

Registered Nurses (RN) assemble information from new and current residents on an ongoing basis, do assessments and engage in various administrative work (collating reports, circulating knowledge, attend meetings, etc). The RN may substitute for the LPN in administering the daily flow of medications during vacation or illness when there is no substitute. However, if a nurse takes over the medication distribution shift it takes much longer, since the nurse has to (re)learn the route, the tempo and preferences of residents, for example, taking meds with yoghurt or water, crushed or halved, etc.

The Pharmacist and Nurse Practitioner (NP) roles are not tied to any specific location as they float between buildings and floors. While the pharmacist is an employee of Lawton’s, the NP is salaried. The pharmacist at this LTCF works 20 hours a week on LTC matters such as bi-annual reviews, taking part in the LTC Pharmaceutical and Therapeutics committee (P&T), and addressing insurance and formulary issues with residents. In addition, his work is stretched out doing additional medication reviewing here and at other LTC facilities. The NP activities include assessments, doing medication reviews as special organizational projects (the anti-psychotic project, for example), writing prescriptions, educational activities, administrative responsibilities (for example the P&T committee), and functioning as a backup resource to nurses, LPNs and physicians. These roving HCPs engage with the floor staff, and are seen as authoritative problem solvers.

Physicians attend to the medical needs of the residents through weekly organized visits called Doctor Day. Through a provincial program called Care by Design, these physicians have agreed to be the designated doctor for one or multiple floors and to direct the care of the residents and accept an on-call schedule.

The daily care, however, is unquestionably in the hands of the RNs, LPNs and CCAs. Physicians are designated to lead several project-related activities such as filling out the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment form (CGA), the bi-annual medication review, etc and use their pens and ink to sign off and contribute to the flowing stream of medications. They are self-employed and bill the provincial medicare plan in a piece-meal way.

Finally, residents have significant work and responsibility around their own medical states and burden of treatment. Medications featured as a consequential topic for many of the residents I talked with. The daily work involved by the residents seems largely invisible and unacknowledged (Strauss 1997). As a brief example, I discovered that resident Mrs. J. carefully collected and tended to the discarded MARs so she could keep track of her 20 plus medications, while resident Mr. L. told me that every day he carefully observes and counts his ten morning medications:

"I line them up by shape, size and colour so I know what I am taking. One day other pills showed up and I asked [name of LPN] “what is going on, guys?” Well, apparently the doctor increased this one drug and took another away. Whatever! I have faith in them (resident interview #8).